Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

I am so glad I recently learned of this talk which Buddhist scholar Andrew Olendzki gave at a 2017 conference Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond. I found this presentation so vital that I have transcribed it and am posting it here to share.

What always seems to be missing for me in any AI / machine learning discussion about its development, impact, ethics, and so forth, is understanding the very foundation of human experience. That foundation is the embodied mind. AI is trained on the data of humans who are embodied and affective and evolved. I strongly believe we need to expand the Western empiricist approach, with its heightened focus on language and LLMs, to an approach that considers a Buddhist embodied model of mind. The Abhidharma canon, after all, is based upon millennia of human meditation and mental training of the mind. We should explore how the wellness or wisdom derived from Buddhist philosophy and practice, which brings emotional balance and that contemporary neuroscience corroborates, can apply towards the positive development of AI in all its coming forms (mechanically engineered or bioengineered as sentient beings—the stunning future to come). Thank you, Andrew Olendzki, for articulating a starting point in your talk, Reverse-Engineering the Mind: An Abhidharma Contribution to AI.

Transcript of Reverse-Engineering the Mind: An Abhidharma Contribution to AI

AO: Thank you very much, thank you all for joining. Appreciations to the Foundation’s wonderful inviting us all here.

I’m happy to contribute to this conversation this weekend on artificial intelligence. The perspective I’m taking on it is this notion of reverse engineering, which I understand to be: you find some device, you analyze it carefully and figure out how it works, and then you try to reproduce it.

Well, I think that the early Buddhist tradition of which I’m a scholar—I studied materials written in early phase of Buddhism in Pali and Sanskrit and Buddhist psychology and Abhidhamma—really has a pretty good model of how the mind and body works. And I’m simply wondering who might use this in some helpful ways moving forward in this field.

The methodology of this way of looking at things is first person. In other words, the direct observation of the mind. Of course, we in the West generally in science when we want to learn about the mind, we study other people’s minds, but in early India, they studied their own minds such as by looking at it.

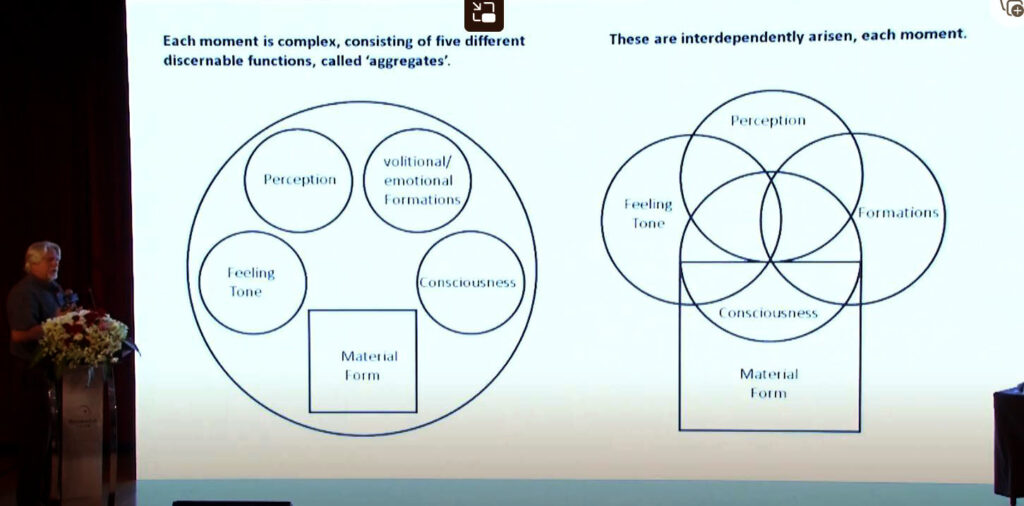

And what was discovered by doing that, as you can discover as well, is that mind unfolds in moments, one after another, and that these moments of conscious awareness may be arising outbound [see Figure 1]. A lot of massive parallel processing in the world and in mind and body, but itself is a sort of linear series, sequence, of mind moments one after another.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

There’s a lot going on below the schema of first-person experience, lived experience. This means going on, you know, atomically, chemically, and biologically, and neurologically, that is far too fast and small for us to have any lived experience on.

Our experience begins at this sort of one scale where these moments of consciousness arise, each one packaging a certain model of information single object, a single set of responses to that object, and they happen one after another in right succession.

They create this world of meaning where they pull a kind of macro construction. This is where we keep track of what day it is, and what time it is, and what we have to do. And this is what many so far this weekend have pointed to as a dream or illusion or native mind only. We’re actually living in a virtual world already, let alone enhancing that virtual reality.

Again, this is access through meditation, so I put them with the principal colleagues of the Buddha, who said to understand [paraphrasing a sutra, see Figure 1] insight into these states one by one as they occur, known they arise, known as present, known as passed away. You, too, can get access to this easily through meditation or simply paying attention.

And there’s no sense at this stage of the tradition of there being a storehouse. No place where the mind comes from or goes to; it’s entirely a process. Mind is an event, not a [inaudible].

The primary model that I think is useful as a sample for an attempt perhaps to create an artificial machine, if you will, are the five aggregates [see Figure 2]. The Buddhists recognized long ago that mental experience is complex and the interaction of several different functions that gives rise to the complexity and nuance.

These five aggregates are really interdependently arisen. All five arise in the same moment as one moment of mind and then pass away, arise and pass away together. So essentially, it’s better to represent them as overlapping and interacting with one another.

Figure 2: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

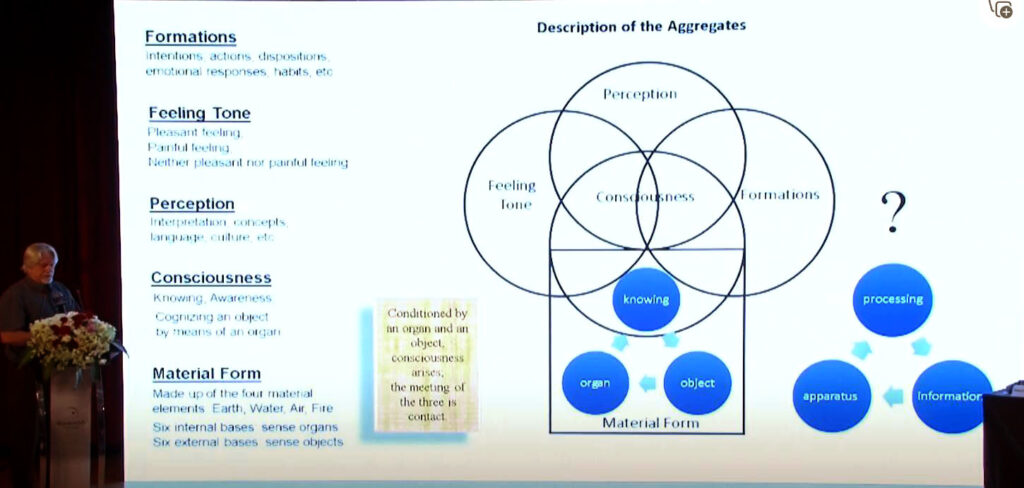

So, let’s look more closely at what these aggregates are. Again to use as a blueprint, if you will, for how we might construct thinking machines [see Figure 3].

Figure 3: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

Material form is simply the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water, or solid with gas and temperature. But also this material form consists of the sense organs within our bodies, because it’s material, and the phenomena of the world that give rise to the information that comes into the system. So, with the organs with which we experience the objects and the source information of those objects, also the material.

And then consciousness, the second of the aggregates, arises interdependently with mind and body. Mind and body arise interdependently. Unlike some religions that would say consciousness is primary and matter derives from that, and unlike a scientist that would say materiality is primary and consciousness arises from that, the Buddhist way to see is interdependent, co-creating one another, mind and body.

The way it’s supported in one of the classical texts, “Conditioned by an organ and an object, consciousness arises, the meeting of the three is contact.” So, this model gives more affinity to a sort of emergent constructivist view of consciousness than some of the later versions of the Buddhist traditions.

The third aggregate [is] perception. This is one of our cognitive capacities. This is the thinking using language and concepts and ideas, shaped by the culture and so on. This is where we try to figure out what it is that we’re seeing. What is it we’re hearing, smelling, tasting, or whatever.

One of the points I’d like to make today is, I think that primarily scientists are very good at this so far. That a lot of machines we’ve created already are good at taking in information and using some symbolic system to try to figure out what that information means.

But the two other aggregates I think are less well understood, less well studied. One is the feeling tone. I add the word ‘tone’ here because I don’t mean the feelings or emotions, simply the hedonic valance. Does something feel good or does it feel bad? Or is it somehow indiscernible to be [known]?

And then there’s the whole emotional component. This is where all our emotions, emotional responses lie. Intentions is the volitional aspect, one chooses and decides, sort of executive function, and all of our personality traits and dispositions and habits and so forth accumulate into these formations.

Now there are a few ways of which I think there might be an infinity between these Buddhist models of mind and contemporary attempts to model consciousness in mind and body.

One is, as I mentioned, this kind of serial process. We’re familiar with that. Another is the fact that these factors all seem to be without self, that in one case is sort of a depersonalized view of events on the horizon, so perhaps we’re all a little bit more like robots than you think.

But also the fact that this basic tripartite structure that part of the consciousness arise in, but maybe they’re similar, just as the knowing of an object by means of an organ, and so also we can talk about processing information by means of some sort of device or [inaudible].

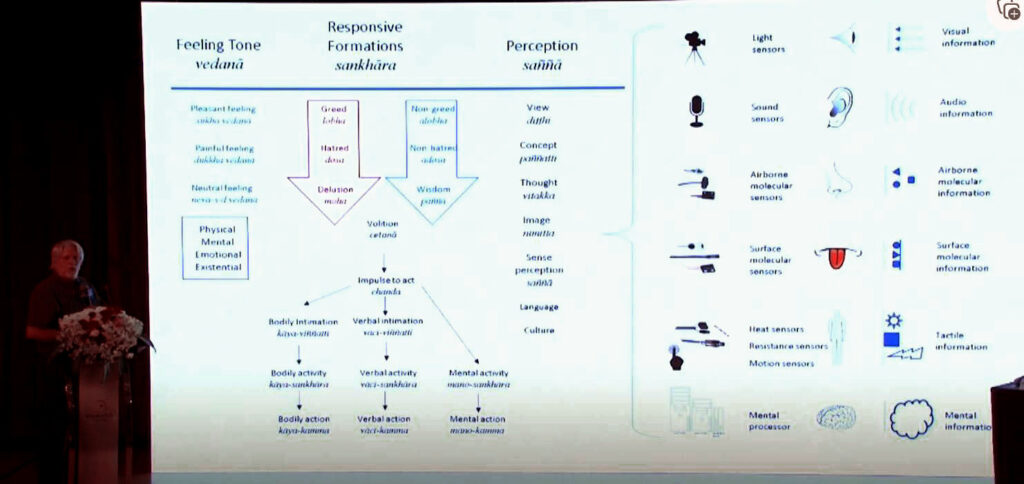

I raise that as a question. I don’t know that these things map onto one another, but they certainly have a similarity. So, let’s try mapping it out a different way [see Figure 4].

Figure 4: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

What we have coming from the world is certain kind of information—video information, audio information, and so forth. The six senses of the body are sensory space apparatus that is sensitized to take in this information and translate it into the language of neuronal activity and so forth.

The five external senses and then the mind is the sixth. I think it would be straight enough to think that we can duplicate them…I’m sure this has been done already. Of course, we have cameras that can see better than us, microphones that can hear better than us, and so forth. And we have the capacity to process vast amounts of information.

But then all this is the baseline that goes into the three aggregates, and so perception, in various words used in Buddhism to recognize perception happening in different moments of scale. The immediate parsing of information comes in the senses, thinking about it that mental information is carried in thoughts that are ruminated upon one after another. And that they call coalesce into views or world views and opinions and ideas that then shape how things are seen and the future.

So again, I think all of this is material that we are quite familiar with and a barometer that we are quite comfortable with. It’s really just figuring out the perceptual and cognitive deep ends and I think our programmers and scientists know these kind of things.

Of course, there’s a response mechanism, too. Some part of these formations are responses to what our aggregates are trying to figure out—what’s going on here, and then our responses, what do we do about it, how do we have to act? So, there’s the mental factor volition, which kind of gives rise to action. This is impulse to act, which allows us to initiate them, and then in various mechanisms they lead down into the performance of action in three different ways. Bodily, verbal, mental.

Even here this kind of stimulus and response system, this kind of input and output, I think is fairly common, fairly pedestrian, and fairly accessible. I think a lot of our devices do this well.

But things become more challenging, both theoretically and practically, when we add this aggregate of the feeling tone. And I think it’s an open question at this stage exactly, what is a feeling? What is actually happening when something feels good and feels bad?

What information is there? How does it manifest in us? This is the embodiedness of being a human being. This is the qualia, what it feels like. This is when you close your eyes and look at these mind moments unfolding. It’s a kind of a tingling, a kind of juiciness, a kind of feeling alive. How would we possibly represent this in any group of artificial intelligence?

I don’t know. I don’t think we can just flood a machine with dopamine under some technological equivalent and that’s going to be good enough. And, of course, there’s the fact that these feeling tones, both pleasure and pain, sukha and dukkha, are not simple, not simply physical sensation but it happens at different levels of scale. There’s physical pain and pleasure. There’s mental pain and pleasure, emotional and even existential pain and pleasure.

These differences allow for the fact that, you know an athlete for example wants to put themselves through a lot of difficult pain for the gratification of achieving the win of the game or the goal or whatever. Or people can be very much in comfort in terms of their physical pleasure might still be very disabled emotionally and in great suffering.

Even using the word dukkha here for a painful sensation there’s a sliding scale where it’s not the same as the noble truth of suffering which is something other than the fact that you stubbed your toe, etc.

So once the feelings come into it, even if there were some way, and again I think this has been neglected, if there’s some way to represent feelings, that immediately gives rise to the emotional responses, the three primary emotional responses. We have a library, but the three primary ones, of course, are greed, hatred, and delusion.

This is where there’s heavily programmed desire into an artificial device. It seems that it has to be in relation to the feeling tone. There’s a little bit of confusion in Western psychology between the feeling tone and the emotional feelings. Or the confusion of course is that we’ve used the same words for them, but the experiential is confusing as well.

I’m not really sure when feeling tone leaves off and the emotional engagement begins, but the minute you have a pleasant feeling, there’s the wanting, the desire for that to expand or continue, the not wanting the pain to be there, and so forth.

And then in the Buddhist model what’s healthy is these unhealthy emotional states—that’s why they’re in red—are sort of flooding into consciousness. Consciousness itself doesn’t carry a lot of diversity, a lot of complexity. It’s merely mirroring, like a mirror, what’s going on outside. Whatever object appears is the cognizing of that object.

All the complexity and drama in the human experience comes from the emotional influence upon consciousness, with all these colorings and textures and flavors and so forth. So, when greed, hatred, or delusion, in some combination or individually are present, their contact taking over the whole intentional apparatus, and then the actions that we do are harmful acts, are cruel acts, are actions that cause suffering for ourselves and others.

Fortunately, of course, these are balanced out with positive emotions, healthy emotional states. Non-greed or generosity, non-hatred, kindness and wisdom. And these, too, can take over and direct and flood the intentional responses.

So, the other factor is that these groups are not polarized at the same moment. And every single mind moment is discrete. It has one set of five aggregates so that means it has a single object and a single emotional response. You can fluctuate very quickly between many different ones, one after another, but in the same moment there can only be one.

So, the issue is really how volition, how decisions are made every single moment whether we want to or not, whether they’re conscious or unconscious, how this volition is going to be influenced by our emotional life.

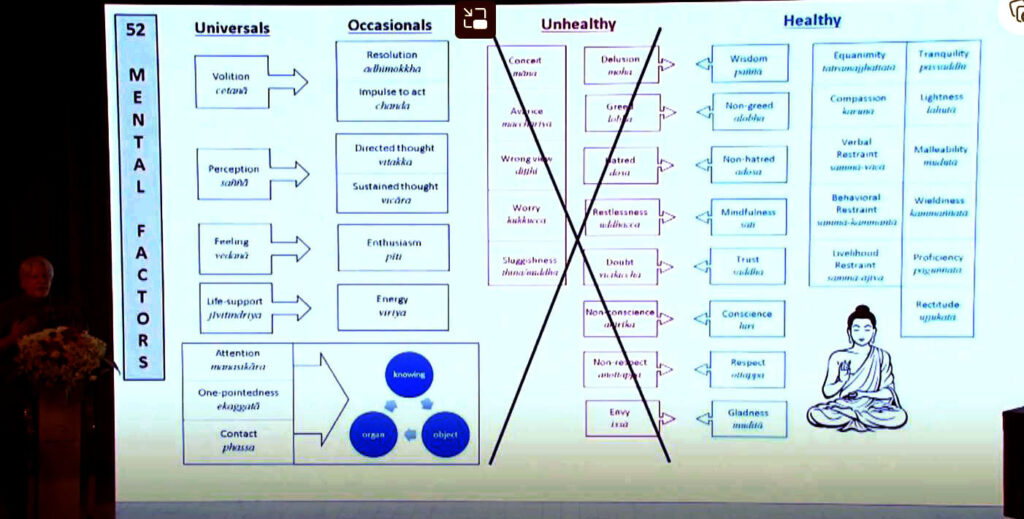

To map this out slightly differently going to the Abhidhamma now [see Figure 5], how this volition is going to be influenced by our emotional life. To map this out slightly differently going to the Abhidhamma analysis which is a slightly more developed phase of this Buddhist psychology, they have this notion of 52 mental factors, 52 of them are aggregates and 50 of them are sort of the diversity and complexity of the emotional initiation of action.

Figure 5: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

And then these three [attention, one-pointedness, contact] I think work together to help bring cohesiveness and focus to a single mind moment for creation of the knowing of an object by the means of an organ.

So, these are always present single mind moment, and then there are some that are occasional. These may or may not occur. And it might good to say this, but I think [inaudible] to build upon the earlier ones, where the volition can be either very resolute and it can initiate actions. The perception can be intentionally guided and consciously guided and we’re going to think things on purpose. Potentially you can hold your attention on a certain object, as we do with meditation on the breath or whatever. The feeling tones can be magnified into enthusiasm and joy, and energy and bringing basically voltage to the system, if you will.

Now these are all ethically neutral. In other words, there’s no doing good or harm in any of this. The attitude where those things come in is with the unhealthy emotions— greed, hatred, and delusion are the main three—but there are a number of moments. There are only 14 of them in Abhidhamma system, in the early Abhidhamma system.

There are only 14 that we have to overcome in order to be well and awaken. But again, anytime these things are functioning they’ve taken over the system and we are not only experiencing suffering ourselves but we’re causing suffering for others anytime.

But the trouble is that they’re effective. You know, many people say, well, anger is useful. You know, gets things done, it gives you energy. Yes, but the Buddhists were never so concerned with what we do with our mind, as with the quality of our mind that exudes from that action. And that’s where a lot of harm can be done, often inadvertently.

Now, fortunately, we also have again healthy factors which counteract these. Non-greed, non-hatred and wisdom, and a whole host of other ones that co-arise with them. Again, in various combinations and various complexities which we won’t get into.

Now, the key point that I want to graze by all this is to simply ask, if we are creating a, trying to create a human device that mimics a human being, how do we incorporate these two aggregates that are generally overlooked?

The aggregate of the feeling tone and the aggregate of the emotional engagement with what’s happening, often in conjunction with the feeling tone. And the critical question is, are these red states—greed, hatred, delusion, and their compatriots—are they requirements? Are they necessary parts of the system? Or can we program our devices so that they don’t have them?

What if we created an intelligent device that did all that clever processing of information, but only incorporated healthy states? What if greed, hatred, and delusion and so forth were not necessary? And we just cut them out of the system? In that case we’d actually be creating an enlightened device because the critical definition of nirvana or awakening in early Buddhism, is not so much some magnificent transformation of consciousness, although we’ve been hearing much about that these days, but it’s really just defined as the cessation of unhealthy states. The cessation of greed, hatred, and delusion. That’s what nirvana is. So, if we can create a device that is without greed, hatred, and delusion, then we’ve created and awakened life.

Now it may also be the case, though if my suspicion is true, that we can’t do this that. That greed, hatred, and delusion, and their associated states, are actually providing something very important to our operating system. We’ve certainly been around for long, long time, as a species and probably all the others, and so maybe there’s something about it. We can’t learn, we can’t get motivated, we can’t grow and evolve unless we’re somehow driven by these defective if harmful states.

So, I end with the trial question, what is it that we’re going to create here [see Figure 6]? Are we to create robots, which we’re already doing, with greater and greater sophistication? But the places that basically process information are ethically neutral. They’re not humanoid, they’re not human-like, because they lack the feeling tone and the emotional complexity. They might have an action response, but not one that is driven by these attitudes that are healthy or unhealthy. Or are we going to create monsters? If it turns out that greed, hatred, and delusion are a necessary part of the equation, and we build it into a machine, especially a machine that becomes quite capable in some way or another, then I find that a terrifying question.

I mean, we know how nasty human beings can be, driven by these primordial toxic forces. If we have to build those into our machinery, then I think there is a really serious danger ahead of us. Because it’s one thing for a machine to do harm to delusions. A bulldozer runs over a furry animal because it doesn’t see it or it doesn’t know any better, or it’s programmed not to care. But if you have a machine that actually can manifest human malice, human hatred, human cruelty, then that’s a tremendous threat to us.

Figure 6: Screenshot from Andrew Olendzki presentation at Buddhism, Science & Future: Cyborgs, Artificial Intelligence and Beyond, Shanghai, China, sponsored by Woodenfish Foundation, 2017.

Or if we’re able to design machines that don’t have these traits, then we’re actually creating sages. We’re creating enlightened beings. We’re creating a whole range of devices that care deeply for us. They want to be kind to us, compassionate, want to help us. They’re incapable of dishonesty. They’re incapable of cruelty, and they could be a tremendous benefit for humanity, to be accompanied by devices that help us in all the ways that are helpful.

And then the fourth option, of course, is that we create persons like ourselves. That is, devices that incorporate both healthy/not healthy components and then the issue becomes, we’re really in the same boat they are. How do we learn to minimize the impact of the things that does harm within ourselves. How do we learn to maximize and develop those qualities that help us out, and so forth?

So, I don’t know what’s going to happen. None of us do. But just one final remark. I know I’m out of time. Just from what I’ve heard this weekend, I think that this kind of use of technologies to alter humanity is upon us and rushing in on us. I think that’s going to happen no matter what. So, I see this not so much as, What is the future of Buddhism? Is Buddhism is going to transform itself so if you use all these devices to help us get awakened? I see rather that this is going to be happening out there in the world, and the question is, Is that process going to be guided and informed in some ways by the fundamental Buddhist values? The values of kindness and generosity, care and compassion and wisdom over greediness and hurtfulness, and so forth?

That I think is the more pressing question upon us. I certainly hope it goes well.

Thank you very much [Applause]