Sept. 23, 2013

Like Lamayuru Monastery’s Indo-Tibetan Senge Lhakhang, Mangyu Monastery’s Vairocana temple is also a small intimate place. Classic, pre-13th century, early period architecture, the site is nestled in and integrated with a village as opposed to fortified and atop on a hill from the community.

I believe that up till fairly recently, let’s say last twenty years, there was no motorable road up to Mangyu Village, which means it was largely isolated and unknown by travelers. We parked a little below the village and walked up to the monastery, passing by small grocery stores that had countertop service for a simple meal of packaged and flavored maggi noodles (what we call ramen noodles in the U.S.) I was starving and grateful to be served one! When traveling around these more remote parts, one never knows where and what the next meal may be. This village had no restaurants or dhabas, nor did I see guesthouses. This is lovely because it indicates that tourism hasn’t bloomed here. Mangyu is pristine for this reason.

Tourism is a challenge to local and modest communities here in the Himalayas. While it brings income, it also brings ecological stress. And ecological stress is no small thing to cope with when the land is semi-arid and mountainous, the people mostly poor, the government ill-equipped to provide adequate infrastructure. The need for food and water sources, sewage, sanitation, and modern transportation to serve tourists often ravage the natural beauty here.

Especially if it brings non-biodegradable garbage like plastic. It’s very upsetting to see packaging or other plastic objects thrown over the side of a Himalayan mountain or floating through the streams, stuck in rocks. Indeed, the Himalayan areas I’ve traveled to have dumps located on the mountain side. You can often see them along the road while driving on the highways. It will be a sudden burst of packaging color en masse among the earthy rocks and otherwise scenic beauty. It’s either this or shopkeepers and townsfolk simply burn the garbage. Yes, they burn it, open-air, in front of their shops or homes, frequently plastic and all.

Plastic bottles and those plastic carton drink containers, potato chip and candy wrappers are the most noticeable litter in the streets. I sadly think, these things will never degrade into anything that can be absorbed properly here. Nor anywhere on Earth for that matter, but since we are here on the topic of the Himalayas, my point is that tourism causes environmental strain and damage. I always ask for boiled water at hotels to cut down on the plastic, and carry a thermos with me. Of course, on some occasions, I can’t avoid it and will guiltily buy water in a plastic bottle.

But my visit to Mangyu Monastery was not one of these occasions, I’m happy to report!

In the 11th century Indo-Tibetan tradition of The Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo, this altar in Nambarnangze once again features Vairocana in the center, surrounded by the Dhyani Buddhas, offering goddesses, animals, and ornate scrollwork, topped by a garuda. See floor plan here.

Experience the interior of this rare, medieval Vairocana temple by seeing a walk-through video here.

Mangyu Monastery Nangbarnangzad

For further info on Vajradhatu Mandala structure upon which early monasteries of this period were based, see this post on Lamayuru Monastery’s Senge Lhakhang and this one on the celebrated Tabo Monastery’s Tsug Lhakhang.

The small Vairocana temple is symmetrically painted on its left and right side walls with one large central Vajradhatu mandala each, flanked by smaller mandalas of related divinities or protectors. On the right side wall, the paintings look like well-conserved oe well-preserved original Indo-Tibetan.

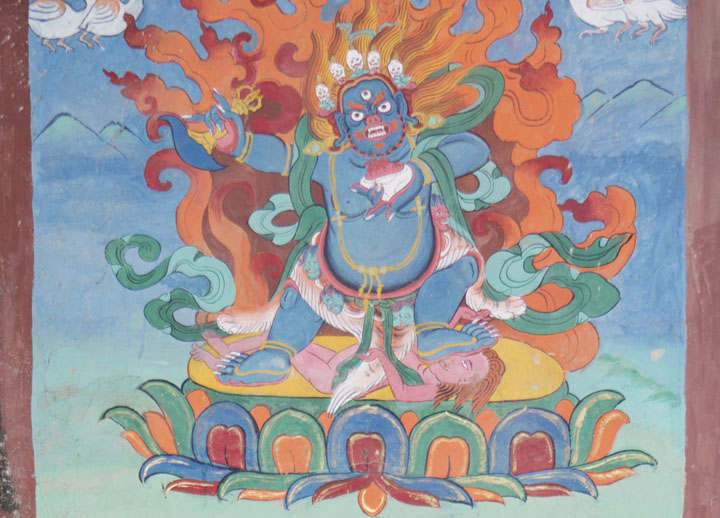

On this entrance wall, however, most everything has been repainted. Peter van Ham in his book Heavenly Himalayas: The Murals of Mangyu and other Discoveries in Ladakh, published recently in 2010, gives a very different description of the state of the protector deity painting above the door.

He writes, “The entrance…is protected by a wrathful blue deity, painted above the door. Only the right half of the painting has been preserved, the rest has been washed away by water leakage through the roof…As two peculiarities the protector is adorned with beautiful shawls displaying typical Ladakhi tie-dye patterns and in his right hand he holds a knife with an interesting blade of Indo-Iranian shape, the tip of which is equipped with a vajra-like structure.”

The discrepancy between van Ham’s description and the above photo shows that this Mahakala was certainly repainted in the last few years. As we can see, absent are the shawls with Ladakhi patterns. This evidence, along with mismatched colors and less refined execution, leaves me shocked and deeply saddened over the handling of Mangyu Monastery preservation.

While the colors in this repainted mandala on the left of this entrance wall are more in keeping with extant original murals, the execution looks nothing at all like the sophisticated, skillful, and expressive handling of Indo-Tibetan artists.

The same is true for the left side wall. What van Ham describes of the 11.5 foot diameter mandala that dominates this wall does not match what currently exists. This must also be a recently repainted mandala.

When this is what an example of original quality and style looks like (click on second image on the bottom) the quality and style of this repainted example pales in comparison.

This small Buddha mandala is on the left of the altar wall. It contains some original and repainted areas.

Here is a side-by-side view of what appears to be an original Indo-Tibetan Buddha in center next to a contemporary repainted one.

The historian David Snellgrove wrote in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan Successors, “The absence of all Buddhist wall-painting in India apart from the Ajanta Caves represents an enormous loss for the history of Indian art. Some deductions can be made from fragmentary remains in Central Asia and especially from the earliest surviving Tibetan murals from about A.D. 1000 onward, and from miniature paintings on Pala manuscripts of about that date.”

While Mangyu may still be pristine from a tourist/environmental point of view, it is less so from an art-historical one. Like I fear for Tabo, Alchi, and other remaining monasteries that have Indo-Tibetan significance, these beautiful, rare wall paintings are disappearing not only through age and exposure to natural elements, but also through the unexpected hands of man. The resultant replacement paintings, lacking in comparable quality, style, etc., are functionally erasing historical records. The originals are thus disappearing over time due to lack of proper conservation and restoration.

All photos © 2013, Eva Lee.

Thanks for the info on Mangyu. Hoping to visit this summer.

Thanks for reading and for your comment. I wish you a wonderful trip there!