September 4th

Our first day out to photograph was at Dhangkhar and Lhalung Monasteries. Both places granted permission because of local and monastic support. I was on my first documenting journey, and how positive an experience it was!

I’ll let the images speak for themselves, but it bears saying that Dhangkar was an original home of the ruling Spitian kings over a thousand years ago, built on a ridge and rock outcrop as a fortress. It clings to the mountain with its whitewashed buildings and traditional thatched roofs. Some buildings seem to be built one on top of the other.

The interiors are navigated by narrow stairs (more like ladders, they’re so steep) and often low-ceilinged passageways. And when you scramble higher and higher, some stairs lead to the rooftops where you climb some more, on gravelly footpaths next to sheer cliff drops, in order to get into other adjacent buildings. Whenever you step outside, you are stunned by the incredible panorama of Spiti Valley in its splendor before you, dotted by the verdant, partitioned farmlands below, and the rigor of the sun casting impressive shadows across the mountain ridges.

Inside the Dukhang, which was the former assembly hall for monks before the new one was built a few years ago, sits a life-sized statue of Vajradhara, the “Diamond Being” who sees the ultimate nature of reality. One who does so is said to have wisdom, or right view.

In the lower level Kanjur Lhakang (library containing Buddhist scriptures) are three wooden figures: Lama Chodrag, Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, and Maitreya, the future Buddha. On the walls are faded and sooty murals, which one can barely see. It’s easy to understand from these murals alone why in 2006 Dhangkar Monastery was named by World Monuments Fund as one of the 100 most endangered sites in the world.

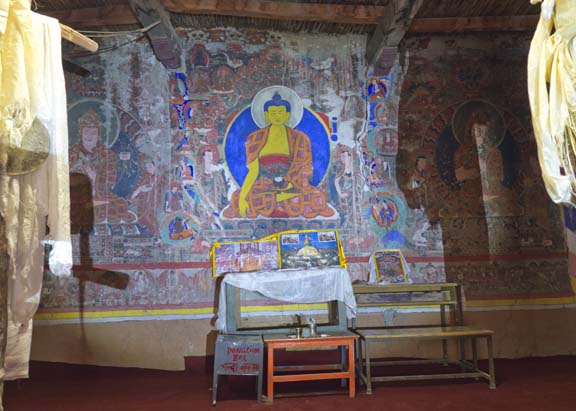

In the uppermost building of Lha O-pa Gompa is Lhakang Gongma, which has the most to see in terms of murals. Its central back wall dominates with Shakyamuni, Je Tsongkhapa (the reformer and Gelugpa founder of the 14th century), and Lama Chodrag.

The adjacent walls depict various manifestations of Buddha. I was struck in general by how varied the paintings are in terms of color, style, and deterioration. It’s clear evidence of selective repainting over the centuries. In the back central wall, for example, Shakyamuni is obviously brighter and more saturated in color than the other two figures. According to Peter van Ham’s book, The Forgotten Gods of Tibet: Early Buddhist Art of the Western Himalayas, only a few of the paintings have been left untouched. The rest stylistically suggest a date of around 17th century.

Of note in the murals is the frieze below the main figures, which largely depicts the life of Prince Siddartha, who became the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. Tabo Monastery has a similar frieze in its Tsug Lhakang, the main assembly hall. Much of it is faded but the below two images are readily identifiable as the life of Siddartha at the palace of Kapilavastu, and the death of Buddha.

We were told by locals that Dhangkar is older than the famous Tabo Monastery because, as the ancient home of indigenous kings, it contained a private temple from before the time of The Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo, pre-dating 10th century. Indeed, at the very top of the Dhangkar citadel are the remains of the palace, which you climb up to through a sleepy and steep quaint village that looks like it has maintained its same way of life for millenia.

Later in the day, we went to Lhalung Monastery. I really loved this small temple pictured below.

Lhalung Monastery, believed to be founded by The Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo, late 10th century C.E., was quite impressive. You enter through a narrow passageway to get to its Serkhang, which means literally House of Gold, but more often referred to as Golden Hall. Attached to its walls are sculptures of deities and other Buddhist personages. Three-dimensional figures in relief against the interior architecture of Buddhist temples are a distinctive feature of Indo-Tibetan artistry in Spiti and Ladakh areas. Similar ones are found at Tabo, Alchi, and Mangyu Monasteries.

Experience the rare and beautiful interior of Lhalung Monastery’s Serkhang by seeing a walk-through video here.

[vimeo 135515512 w=600 h=337]

Once inside, the splendor of the ornately gilded and polychromed clay figures strikes you. The sculptures fill the temple practically from floor to ceiling. There are over 51 figures mounted on the walls or placed in the temple, arranged in mandala formations on each wall. Geshe-la said that these types of cantilevered relief sculptures are specific to the Trans-Himalayan region and are not found in Buddhist temples anywhere else.

On the central wall is Shakyamuni in the middle, flanked by two elaborate groups of five figures, each dominated by a deity–identified as Dharmadhatu Vagishvara, a complex form of Manjushri on the left, and Vajrasattva on the right. These figures are set in architectural alcoves, while the others are contained within lotus motif scrollwork, accented by decorative animals and dancers.

Visible below is the right wall with sculptures arranged in a Prajnaparamita mandala, with Vairocana in the center surrounded by four Dyanibuddhas or Buddha-families: Ratnasambbhava, Akshobhya, Amoghasiddhi, and Amitabha, and their female attendants.

On the left wall (photo below) is a Vajradhatu mandala arrangement around the three-faced and eight-armed Saravid Vairocana. Around him are the 16 deities in his cycle, including once again the Buddha families of Ratnasambhava, Akshobya, Amitabha, and Amoghasiddhi.

So now, that’s a lot of deities in one small temple! Their plethora really conveys not only aesthetic richness but also the complexity of Tibetan Buddhist tantric practice. What do all these deities represent in these mandala arrangements? Put simply, mandalas are visual guides for a practitioner in their meditation. They are aids in the realization of the true nature of mind and reality. As an oral and esoteric tradition, one needs a lineage teacher. Experiential understanding of this leads to liberation from conditioned existence–that is to say, leads to enlightenment or nirvana. Here is a succinct description of what the Five Buddha Families represent.

Geshe-la had said that the temples in these areas really demonstrate only the lower three tantras, not highest yoga tantra, which is mainly what Tibetan Buddhists practice today. The lower three are more concerned with purification, whereas the fourth level is actualizing self and deity, and therefore, enacting profound experience and understanding of emptiness. In The Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo’s time, late 10th century, focusing on the three lower tantras was a way to go back to roots and revitalize/reform tantric practice in Tibet which had grown distorted. This was partly the reason for the enormous interest in the original texts and their teachings, translating them from Sanskrit to Tibetan.

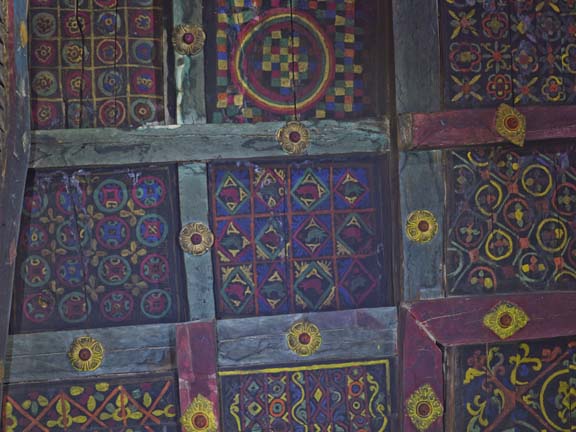

Lastly, the coffered ceilings were painted with delightful and folk-looking decorative motifs. Now I know what scholars mean when they speculate that these must reflect 10th century Kashmiri–influenced textiles.

All photos © 2013, Eva Lee.

Both amazing and beautiful .

Wow! Breathtaking and peaceful… you must be thrilled by it all and that’s probably an understatement!

thank you Eva,

these are great shots, am learning alot about these murals through your blog

the colors are so rich, amazing to see in such a remote location, that color is so important

Magnificent! And congratulations on being a Fulbright scholar. Thanks for the Like on my shell gold post – keep in touch, I am always interested in discussing pigments with fellow artists.

Anita

Thank you, Anita! I came across your blog when I searched for pure gold paint. I understand there is a 24k product that Tibetan painters and sculptors use that comes from Nepal only. An artist here described it as the gold coming in pebble form and you make paint by adding water and glue (perhaps gum Arabic?)

The artist may be referring to a pebble of compacted powdered gold, to which you need to add gum. Prabably made in the same way as I described on my post – because there is really only one way to make gold that you can paint on with a brush.

The other technique is gilding with gold leaf, where the surface is prepared with a water or oil based medium, onto which small sheets of gold are floated. Very skillful – I am still trying to learn that technique!

Anita, gilding is what I know how to do, which is why I was so curious as to the methods Tibetan artists use because theirs is a painted water-based technique. I have since learned that they use animal glue to mix with the gold powder. Thanks for your reply and sharing info!

Ah! Forgive me for not realizing that you are a gilder! I think that the pepple gold you mentioned would still have to have been ground by the traditional shell-gold method – where manuscript painters used mostly gum arabic (and maybe glaire in europe?) the Tibetan artists use animal glue. I guess that would be some fine quality skin glue, as opposed to the heavy hide glue. I once observed a Japanese conservator working on Rimpa screens at the British Museum – he used deer-parchment for the glue. It is much more hardwearing than gum.

Hi Eva, me again – I have a question about the red used by these Tibetan artists – I know that they use Mercuric sulphide (cinnabar) – there are all sorts of ayurvedic implications about the colour in India – is there a comparative narrative around the substance in Tibetan traditions?

Yes, for thangka paintings, Tibetan artists use a more refined clear animal glue that also comes in pebbles. For other purposes such as murals, they use heavier hide glue which comes in sheets.

If I learn the answer from Tibetan artists, I’ll let you know!

Thanks Eva – I would be very interested to know! I am doing some more research about the colour at present.